Victor Farra private In the first Infantry Battalion, was among the many first to land at Anzac Cove before dawn on 25 April 1915.

© Commonwealth of Australia (National Archives of Australia) 2024, CC BY-NC-ND

In the chaos, Farrar disappeared. When the primary roll call was made on April 29, he was nowhere to be found. Her record was amended to read “missing,” which is guaranteed to send any parent right into a blind panic.

By January 1916 it was determined that Farrer had been killed in motion in Turkey sometime between 25 and 29 April. He was 20 years old when he died.

His mother, Mary Drummond, spent months in agony waiting for news of her only child. His initial respect for the authorities quickly gave option to frustrated and offended correspondence. They wrote:

Now, sir, I consider it your duty. […] When a mother gives to her son. […] When that son is injured, he must have some news.

By October, he tried to enlist the assistance of his local Member of Parliament, His vow To know if his son is alive.

But it was not until 1921, six years after Farrer was last seen alive, that the military admitted that a radical inquiry had did not locate his body. They Answered:

I wish you’ll tell me that in case you had known that he had been buried, my sorrow wouldn’t have been so great.

Fur's name stands on a panel Lone Pine Memorial to the Missing At Gallipoli, with more More than 4,900 Among his Australian colleagues who likewise don’t have any known graves.

A heavy price

About half of Australia's eligible white male population voluntarily enlisted. 1st Australian Imperial Force Between 1914 and 1918.

Of the 416,000 who joined, greater than 330,000 men Served overseas. of them, More than 60,000 won’t ever return. These are the best casualty figures for any belligerent nation in the whole war.

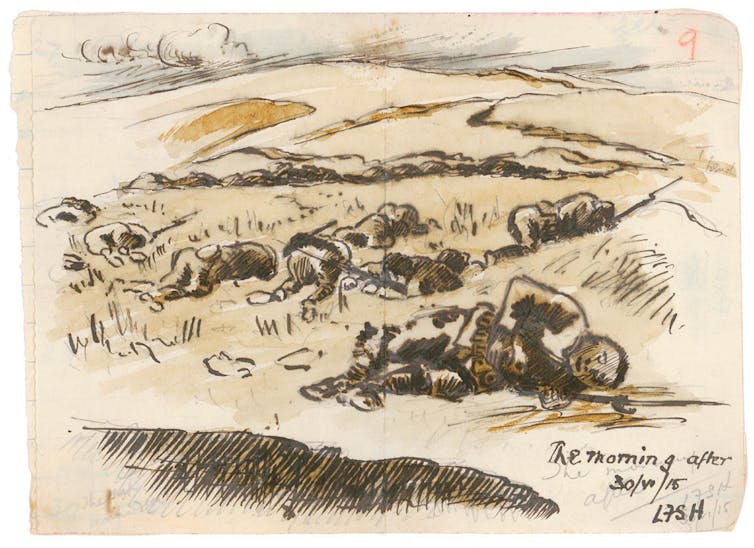

Leslie Hoare/Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

More than 80% Among the Australian soldiers were single like Farrar. In some rural communities, this rate was About 95%. So the burden of grief fell on the shoulders of the old parents.

The impact of wartime bereavement on aging parents was profound. For some, grief became the important focus of the remainder of their days. For most, the memory haunted them within the years after the war, and for all, the war became a serious event of their lives, after which nothing could be the identical.

Some ended up in mental hospitals.

Many parents' physical health There was a rapid decline When he heard that his son had died. An example was Catherine Blair. They Died unexpectedly On the primary anniversary of his son's death in France on the age of 54 from heart failure.

There was evidence of moms and dads being violent, having suicidal thoughts, being the cause Public nuisanceand switch to alcohol of their distress.

As I actually have described. My PhD thesisMany working-class moms and dads joined the wards of public mental hospitals, comparable to Callan Park in Sydney. Some stayed there all their lives.

Adam.JWC/ Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

The psychiatric files I reviewed from several major mental hospitals found evidence of delusions, hallucinations, and complete denial of my son's death. Some had lost multiple son.

Upper-class families avoided the stigma of public mental hospitals, as they might see private doctors, and receive nursing help at home.

Especially the upper class fathers appointed themselves as guardians of their son's memory. She has spent immense time, effort and funds lobbying the Australian government and producing commemorative books and memorabilia to acknowledge her son's services. Maybe it was one A sign of obsessive griefbut not available to a working class family.

How has mourning modified?

Death and injury in the course of the war touched every a part of the country, from cities to hamlets, from towns to stations.

The scale of the damage was as shocking because it was unprecedented, and altered permanently. The Culture of Mourning Exercises in Australia

Funeral services and conspicuous displays of mourning varied in accordance with class. Overall, nevertheless, the Australian experience of death within the nineteenth century was based on traditions prevalent in Victorian England – attendance on the deathbed, a graveside funeral service, headstones and inscriptions, and the placing of flowers or other memorials. The physical act of going to the grave. on special occasions.

It was also customary to decorate in mourning black and for wealthy families, to parade the deceased through the streets with many horses to indicate their social status and piety.

Aussie~Crowd/Flickr

However, mourning within the comfort of those familiar rites required two realities – knowledge of how and where their loved one had died, and the presence of the corpse.

Neither was available to bereaved in Australia in the course of the Great War. These established, reliable patterns were stripped away.

Instead, and with many who were bereaved, the notion of claiming damages in public was seen as tasteless and frivolous.

Instead of public displays at funerals, they became private affairs for family and shut friends.

Grief was endured and expressed in public with a performance of dignified stoicism inside the privacy of the house. The custom of wearing mourning black is gone.

An estimate 4,000-5,000 War memorials were built across the country. These became a focus for communities to honor their dead and remember their sacrifice, a practice we still see today on Anzac Day.

Leave a Reply