Travelers all the time face health risks when away from home. Medieval people were no exception. Pilgrims, Crusaders and others Be warned “Perils on land, perils at sea, perils of thieves, perils of hunters, perils of battles” by Thirteenth-century preachers corresponding to Jacques de Vitry.

There were also health risks: disease, malnutrition and dehydration, injury, accident and poisoning. Medieval travelers were proactive and revolutionary in trying to forestall unwell health while away.

Although the adjective “medieval” continues for use to indicate a backwardness in medical and scientific knowledge, this history of preventive medicine shows us something different.

From good sleep to 'good' leech

There is a very interesting set of practical health care instructions for travelers (on travel procedures and manners for travelers). The text was composed around 1227-28 by Adam of Cremona for the German Emperor Frederick II, who was about to set out on crusade.

Unedited and Surviving in a single manuscriptToo much attention on Adam Ibn Sina's Eleventh-century Canon of Medicine, used for medical education in medieval universities.

Adam suggested that bloodletting (phlebotomy) be performed before the emperor's journey and commonly thereafter depending on the “will and mood” of the celebrities.

Bloodletting was central to medieval medical practice. In this, leeches or sharp knife-like instruments were used to open the vein and drain the blood from the body. It was performed as a preventative and, within the case of some medieval religious communities, periodically as a part of monastic physical discipline and discipline.

Devoting about 25 chapters of his text to phlebotomy, Adam draws on the concept bloodletting humor (Four fluids thought to make up the body: blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm), expelling “bad” and balancing the body to arrange for a healthy journey.

Although modern medicine has since abandoned the 4 humors concept, bloodletting and “leech therapy” proceed in some. Medical settings For specific purposes.

Wikimedia Commons/Wellcome Trust

Adam advises all travelers to be looking out for bleeding devices – especially leeches – while on the road. His writing included warnings to differentiate between leeches: good (round and glossy) and bad (black or blue in color and located near water).

He also gave careful instructions on tips on how to purify water, in addition to advice on weight loss plan (the traveler's home weight loss plan with loads of fruit and veggies), the importance of rest and adequate sleep, And the importance of normal bathing. .

Dysentery was a well known risk of travel, especially for crusaders, and Adam's guide reflected the need of all travelers to avoid it by keeping the digestive system in balance.

Balance of body and soul

Knowledge of water supplies was especially vital for travellers.

A Hajj Guide Informed travelers that probably the greatest sources of water within the Holy Land was just outside of Haifa in modern-day Israel.

Theodoric's Guide to the Holy Land Travelers were reminded that there was no water in Jerusalem except rainwater that the inhabitants collected and stored in cisterns for day by day use.

Medieval travelers were also reminded to take special care of their feet. In 1260 Vincent of Beauvais Instruct travelers to make use of poultices (wound dressings) product of oil, plants and silver (mercury) to forestall and manage blisters – a disease experienced by long-distance pilgrims. happens to

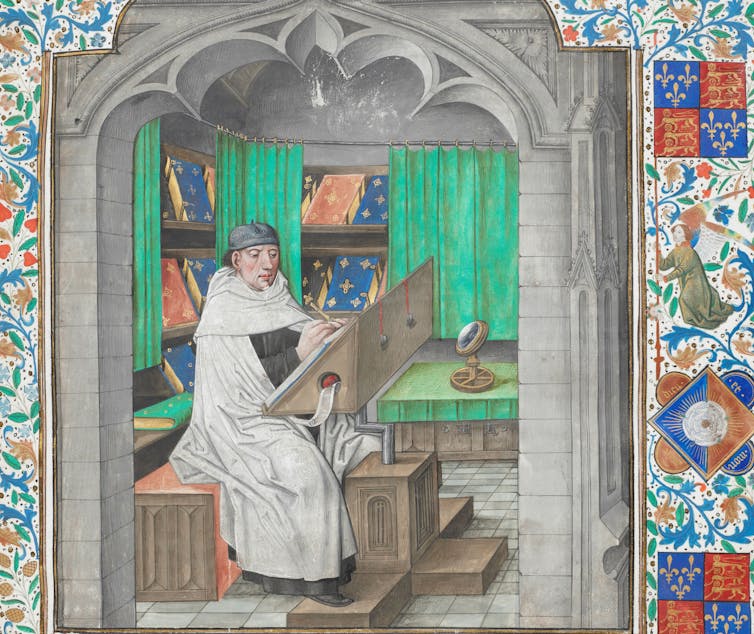

Wikimedia Commons/British Library

Adam from Cremona advises travelers to regulate their speed when walking, especially on unfamiliar and unpaved roads.

The overall advantage of exercise was generally considered. Preachers like Jacques de Vitry told their congregations Movement makes the body healthy. Physically and spiritually, due to this fact must be done commonly before and in the course of the trip.

Different climates and environments meant encountering dangerous animals. The holy land was said to be home to poisonous snakes.

Passengers took with them. Theriacan antidote made partially within the case of snakebite. It shall be eaten on the wound or dirty.

Crocodiles were also often mentioned as a threat in Egypt. There were no antidotes to the attack, but forewarning passengers with knowledge helped them stay alert.

Medieval travelers didn’t leave their fate entirely in God's hands. Even the Crusaders took precautions to balance physical and spiritual health before and through their journeys.

The Met

They confessed sins, asked for blessings to guard their property and possessions and carried with them charms and amulets that were believed to “protect the health of the body and the soul”. An Italian blessing of the 12th century This “divine prophylaxis” of clarity goes hand in hand with a more practical care of the physical body—a holistic view of health as physical and spiritual.

The measures and remedies available to medieval pilgrims and other travelers could seem limited and maybe dangerous to modern readers. But like all travelers, medieval people used the knowledge that they had and tried hard to keep up good health in sometimes difficult conditions.

The desire to be healthy is a really human thing, and its long medieval history reminds us that good health has all the time been as rigorously managed as a cure.

Leave a Reply