We speak about mental health greater than ever, however the language we should always use stays a vexed issue.

Should we call individuals who want help, or? Should we use “first-person” expressions resembling or “identity-first” expressions resembling? Should we label the diagnosis or avoid it?

These questions often evoke strong emotions. Some people feel it means being passive and subservient. Others think it's too transactional, as if getting assistance is like buying a brand new refrigerator.

Proponents of private language argue that folks mustn’t be defined by their circumstances. Proponents of identity-first language argue that these situations might be sources of meaning and connection.

Avid users of diagnostic terms find them useful descriptors. Critics worry that diagnostic labels can pigeonhole people and misrepresent their problems as pathology.

Many of those differences are rooted in stigma and concerns in regards to the treatment of suffering. Ideally the language we use mustn’t forged individuals who experience suffering as defective or shameful, or frame the on a regular basis problems of living in psychological terms.

our New researchPublished within the journal PLOS Mental Health, it examines how the language of suffering has evolved over nearly 80 years. Here's what we found.

General terminology for a category of terms

Common terms – like, or – have largely escaped attention in discussions in regards to the language of mental sick health. These terms consult with mental health conditions as a category.

Many terms are currently in circulation, each with an adjective followed by a noun. Popular adjectives include , , and , and customary nouns , , , , , and . Readers can encounter every combination.

These terms and their components differ of their meanings. And probably the most medical sound, while, and is just not related to health. means in direct contrast with, while a medical specialty means

, a recently emerging term, is arguably the least pathological. It means something to be solved slightly than cured, doesn’t refer on to medicine, and has a positive connotation slightly than the negative connotation of or.

Monkey Business Photos/Shutterstock

Of course, this development points to what cognitive scientist Steven Pinker calls “euphemism treadmill”, the tendency of language to create latest terms (at the very least temporarily) to avoid the offensive connotations they replace.

English linguist Hazel's price Argues that the term has modified rapidly to avoid the stigma related to it.

How has usage modified over time?

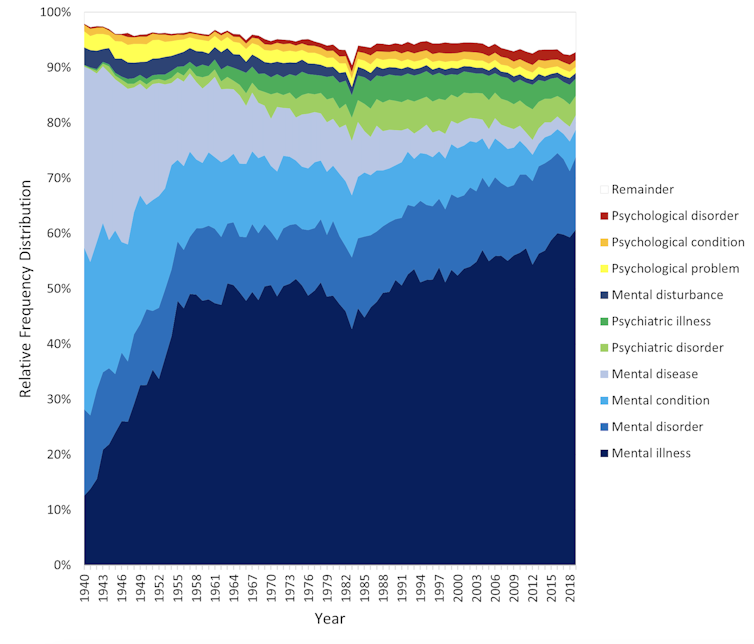

In the PLOS Mental Health paper, we examine historical changes in the recognition of 24 common terms: each combination of nouns and adjectives listed above.

We find the frequency with which each term appears in two large text datasets from 1940 to 2019 representing books in English and diverse American English sources, respectively. The results are very similar in each datasets.

The figure presents the relative popularity of the highest ten terms in a big data set (Google Books). The 14 least popular terms are combined with the remainder.

Haslam et al., 2024, PLoS Mental Health.

Several trends are visible. has consistently been the most well-liked adjective component of common terminology. has turn out to be more popular in recent times but remains to be rarely used.

Among nouns, less has turn out to be more widely used while has turn out to be dominant. Although the official term in psychiatric classification, it has not been widely adopted in public discourse.

Since the Nineteen Forties, clearly has turn out to be the popular generic term. Although an assortment of alternatives have emerged, its popularity has steadily increased.

does it matter?

Our study documents significant changes in the recognition of common terms, but do these changes make a difference? The answer could be: not much.

A study Found people think, and essentially consult with the identical phenomena.

Other the study indicate that labeling an individual as , , , or people's attitudes toward her or him doesn’t matter.

We don’t yet know if there are other implications of using different generic terms, however the evidence so far suggests that they’re minimal.

Pixabay/Pexels

Is 'trouble' higher?

Recently, some authors have promoted it as a substitute for the standard generic terminology. It lacks clinical meaning and emphasizes the subjective experience of the person slightly than whether or not they fit an official diagnosis.

I appears 65 times. 2022 Victorian Mental Health and Wellbeing ActUsually within the expression “mental illness or psychological distress”. By definition, anxiety is a broad concept that is just not synonymous with mental sick health.

But is it insulting, because it was intended? Apparently not. According to A study, it was disgraceful in comparison with its alternative. The term can amplify this and distance us from other people's suffering.

So what should we name it?

Easily the most well-liked generic term and growing in popularity. Research shows that different terms have little or no effect on stigma and that some terms intended to stigmatize can backfire.

We suggest that this must be accepted and the proliferation of different terms resembling, which create confusion, should end.

Critics may argue that the medical frame is imposing. Philosopher Zuzanna Chappell disagrees.. , she argues, refers to first-person subjective experience, not an objective, third-person pathology, e.g.

Properly understood, the concept of illness centers the person and their relationships. Chappell writes, “When I recognize my suffering as an illness, I want to claim a caring interpersonal relationship.”

As common terms go, there may be a healthier option.

Leave a Reply